Democratising Capitalism

Dr Sudhir Rama Murthy is a postdoctoral research fellow with the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship, Saïd Business School.

Democratising Capitalism

Why ESG is inadequate, and a Magna Carta is needed, instead.

Content trigger warning: This blog post discusses colonisation and slavery.

Disclaimer: Views expressed belong solely to the author.

The Milton Friedman Doctrine has guided financial capitalism for the last half-century. While it has successfully maximised profit for investors, this profit has often been to the detriment of employees, communities and the natural environment. There is a growing call to reimagine capitalism that would serve a wider range of stakeholders, a vision that has broadly been termed ‘stakeholder capitalism’. How such a vision of stakeholder capitalism would be realised is an ongoing debate.

ESG: Beauty in the eye of the investor

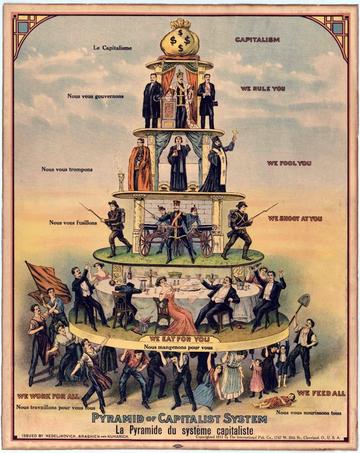

Image: Pyramid of Capitalist System / An American caricature from 1911 (Wikimedia Commons)

A popular approach to stakeholder capitalism is based on reporting the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) concerns in the company’s operation to its investor community. The corporation would transparently acknowledge, measure and report its various positive and negative impacts upon the world, categorising them under the Environmental, Societal and Governance categories. The investor community, of whom asset managers and institutional investors are the most powerful, shall then hold companies to account for both financial performance and ESG performance. Much hope is vested in academic and practitioner circles that an enlightened investor community can help realise stakeholder capitalism. Although well-intentioned, there remain key limitations to this ESG approach.

Firstly, the ESG community remains largely concentrated in the financial circles of the global north. Even in the most aspirational vision of ESG, asset managers on Wall Street would speak to sovereign wealth fund managers in Northern Europe, who would then together persuade company boards in London or elsewhere in the global north to cater to their ESG priorities. They would debate among themselves on matters such as poverty in Africa, deforestation in South America, malnutrition in South Asia, and so on. It is a top-down approach meant primarily for those literate in the language of finance and accounting. This is likely to further concentrate power among the financial sector experts rather than distribute power into the hands of stakeholders around the world. Even more problematic for the long-term, those stakeholders may well be de facto excluded from the debate of capitalism itself, given the technical language of accounting standards, global finance and impact measurement.

Secondly, ESG imposes an inherent conflict of interest upon the investor. Consider the uncomfortable examples of colonisation and slavery. In a hypothetical ESG response, the investors of the British East India Company would be asked to decide whether colonisation is acceptable or not; the profiteers of the slave trade would be asked to determine whether slavery is an acceptable price for the world to pay to generate profits for them. Clearly, submitting an ESG report to those investors cannot be the basis of a satisfactory resolution. While in no way comparing such egregious historical examples to the present, the logic can still be tested. Consider data privacy of users in the digital economy. An ESG response to data privacy concerns would be to submit a meticulous standardised ESG report to the investors of big tech companies. Effectively, the enlightened investors of big tech would decide whether users are entitled to data privacy or not, in order to generate record profits for themselves. ESG unfairly imposes this conflict of interest upon the investor. A fundamental principle of natural justice is Nemo judex in causa sua, that is, no one should be a judge in their own case. ESG breaches this principle by expecting an enlightened investor to protect the interests of other stakeholders, despite holding a personal financial stake in that decision.

Thirdly, the timescales of ESG are disappointing. The proponents of ESG argue that long-term institutional investors, such as pension funds, have a self-interest in protecting other stakeholders from harm. While a fly-by-night short-term investor may look for a quick profit, a patient investor would eschew stakeholder exploitation because such profit would be unsustainable. While this argument is logically elegant, the timescales are flawed. Unfortunately, the timescale of patient capital is in decades while irresponsible capitalism can be both profitable in the near-term imposing negative impacts, and also be profitably perpetrated for centuries. In addition to the two uncomfortable examples of slavery and colonisation already mentioned, one can add climate change to that list. A pension fund could have invested in fossil fuels at the beginning of the industrial revolution and profited for centuries by causing climate change before suffering reputational risks or poor financial returns. The arc of the financial feedback loop – much like that of the moral universe – does indeed bend towards justice, if only an investor’s patience stretches a few centuries long. Alas, that is rarely the case with investors’ patience.

If this top-down ESG approach is inadequate to achieving stakeholder capitalism, one must wonder what an alternative approach could be – an approach that empowers stakeholders against the financial elite, one that does not expect any actor to have foresight or be enlightened, and one that distributes power into the hands of those who would suffer environmental and societal concerns first. Such a bottom-up approach would democratise and invigorate stakeholder capitalism.

An alternate approach: A Magna Carta for capitalism

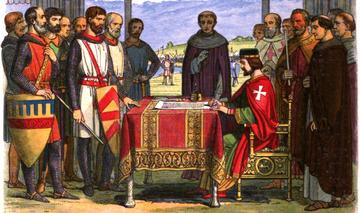

Image: King John in 1215, a 19th C depiction (Wikimedia Commons)

The Magna Carta is a royal charter agreed to by King John with his rebel barons in 1215. It curtailed the powers of the monarch and heralded the development of civil liberties and modern democracy itself. Capitalism is today at a crossroads, with investors seated above company boards, handing down instructions on all matters including stakeholder concerns. What we need is a Magna Carta for capitalism that disciplines the power of investors and empowers the now voiceless stakeholders in substantive ways. Crucially, the corporation is an appropriate unit for implementing this bottom-up democratic approach.

Within a given corporation, the boardroom would be a debating chamber for stakeholders to passionately defend their own interests and work through their tensions. Decisions emerge by stakeholder-stewards reconciling their tensions to shape the operations of the firm. The board would work to appease its own stakeholder-constituents rather than an investor overlord - if one were to stretch the analogy.

An operations management perspective is recommended to help convene such a boardroom. Operations management can help the firm identify its various externalities, understand stakeholder marginalisation, and expand the firm’s responsibility boundary to match its operational footprint. The corporation effectively becomes the collective voice of its stakeholders, seeking investment from the capital market. The investors would still assess the financial viability of the team of founder-stakeholders to creatively turn a profit and resolve any tensions that might emerge in the long-term. But true to the spirit of democracy and principles of natural justice, the investor is not an active participant in the debating chamber itself.

Governing a corporation in such a democratic manner might require the establishment of innovative corporate forms. Future entrepreneurs, say in the technology sector, can then choose to incorporate their enterprises as democratised corporations where stakeholders are empowered relative to investors. This could be discomforting to the beneficiaries of an outdated Friedmanite order but would reimagine capitalism itself.

What next: From naïve optimism to humble pragmatism

There remains a pressing yet unanswered need to reimagine capitalism that can serve a wider gamut of stakeholders. ESG is well-intentioned but naively optimistic in hoping that enlightened investors armed with annual reports shall deliver stakeholder capitalism. Instead, a humble and pragmatic bottom-up approach might be necessary; establishing novel corporate forms would be a helpful start. But the history of Magna Carta suggests that it can be a long and uncomfortable process to democratise power structures, be they political or financial.